The History and Goals of VoidLoop

Revision: 0.1, 9/28/25

Author: Greg Kovacs

I grew up tinkering with electronics and was supported in that by loving parents who provided me with a basement laboratory located in a large chunk of my father's fantastic workshop. I remember many late nights of experimenting, taking apart surplus from WW II and later, and playing with whatever test equipment we could get our hands on. I couldn't get enough, and that fascination with hands-on electronics stays with me decades later. While I chose to study electronics deeply, I have known several brilliant, self-taught individuals including the legendary Jim Williams, who mastered electronics via personal exploration.

After teaching electrical engineering at Stanford since 1991, in the last couple of decades I had been organizing materials to share with the community in the areas of mixed-signal and embedded electronics – most excitingly the combination of these technologies. Along the way, some really great people inspired the path I have gone down, which combines mixed-signal electronics into the "Arduino" ecosystem, which is simple, friendly and thankfully operating-system-free (so not Raspberry Pi type stuff…).

Notably, around 2008, when I was on leave from Stanford and we were living in the DC area, my friend and former student Chris Countryman gave me my first Arduino Uno. I was thrilled at how approachable it was, and at the educational potential. My graduate students and I began using Arduinos in classes. With the kind support of Texas Instruments' CTO, Ahmad Bahai, my then graduate student Bill Esposito developed a full DSP processor "shield" and high-resolution analog I/O shield. Unfortunately, we could not get any interest from SparkFun nor Adafruit, makers of boards and kits for the growing community, so the project did not reach the commercial markets.

Meanwhile, Paul Stoffregen, co-founder of PJRC (https://www.pjrc.com), released the Teensy 3.6, and eventually the Teensy 4.1 which were mind-bogglingly faster than the original Arduino Uno and based on ARM processors. At the same time, James Bowman (Excamera Labs) had released the "Gameduino" display shields that included a simple GPU and were very accessible ways to build fast color graphical user interfaces with touch capability. I knew this was the path. With the Teensy 3.6, I developed a fully-functional FFT analyzer family with a tracking generator and with help from then graduate student Nathan Volman, put the basic unit into a nice laser-cut box as a proof-of-principle of an approachable, working but also hackable instrument with abundant teachable points.

In parallel, and with help from SRI International's Aaron Solocheck, I was able to make port I/O work, which opened up fast ADC's, approaching 60 MSPS. That in turn showed that (at that time using blocking code to read the port) the fast processors in the Teensy's could potentially yield a low-RF bandwidth spectrum analyzer at least conceptually comparing to my old favorite, the legendary HP89410A (this instrument brought fast FFT analysis to the world of traditional spectrum analyzer user feel… wow!).

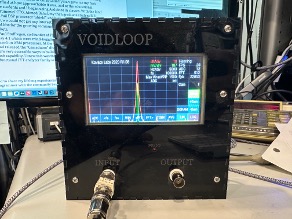

Figure 1: Final version of touch UI spectrum analyzer with tracking source, based on the Teensy 3.6 and Gameduino display.

Well, nobody predicted COVID-19, the semiconductor shortage, nor that this in turn would lead to the demise of by beloved Teensy 3.6 (which, thanks to the MK66FX1M0 processor) had two on-board, fairly decent DACs for signal generation). Darn! (Side note, at the time of writing this, the chip is in stock at DigiKey, and I wonder if there is going to be anyone who brings the Teensy 3.6 back to its adoring community…) Also, the Gameduino displays from Excamera Labs were out of stock, with no way for us to know if they would ever be back, although now they seem to be. In any case, the strange "Arduino-shield" footprint was always something I wanted to move beyond. Lessons learned, as always, about ensuring ongoing supply before designing, or at least purchasing bulk stock to allow production for a good length of time.

Soon, but still with no reliable supply of Gameduino displays, I adopted the Teensy 4.1, which was reasonably available during this difficult period of time. Then, after getting port IO again sorted out (not easy), I ported my FFT analyzer code successfully. After reading about DMA on the Teensy 4.1, I was excited when Mark Flamer (then a consultant to Triple Ring) demonstrated that one could use the DMA engine with port IO for this purpose. With this option, I designed a prototype board using the Gameduino, 40MSPS 10-bit ADC, DDS waveform generator, and all of the necessary support circuitry (Figure 2 below). Until then, one could not easily use external ADCs in this way, but for internals, the path was paved by Pedro Vilanueva ("Pedvide"), who produced a fantastic DMA ADC library for the Teensy processors (https://github.com/pedvide/ADC). Our custom DMA library for external ADC's, written from the ground up by Zachariah, should be ready for its debut by the end of this year or early next year.

Figure 2: Prototype FFT analyzer using a 40MSPS, 10-bit ADC and earlier DMA code.

With all of this proof-of-concept work, I knew we could bring a very low-cost family of educational boards to the community. Now, caught up to 2025, I have partnered with Zachariah Magee to realize my long-term vision. After much testing, I decided to use low-cost, available and GPU-less color LCD touch displays, notably the ILI9341 for the time being. With that decided, we could pursue a series of very low-cost boards for teaching, hobby use, and so forth, starting with a bare-bones board consisting of the ILI9341 320 X 240 color touch display (also with basic support for the Newhaven displays that are equipped with the same family of GPUs as the Gameduino and can use the same codebase, an example being the NHD-5.0-800480FT, which has 800 X 480 pixels, capacitive touch, but also a much higher pricetag), a pair of rotary encoders, socket for a Teensy 4.1, and abundant prototyping space. With this baseline board and Pedvide's library, an 800kSPS (1MSPS results in a lot of harmonic distortion in the ADC, unfortunately) FFT analyzer at a minimal cost. Out-of-the-box code will allow quick and satisfying demonstration of the various features and teachable points, and Zachariah has done a really great job of translating my vision into professional, tested and approachable code.

More on all of this later, but the vision going forward is to roll out some very cool software and hardware toward the overall goal of sharing some of my key learnings as both a practicing electrical engineer and as a professor. The main topics I would like to make more accessible to the community include:

- The interplay of analog and digital circuits, which have a flexible boundary, modulated by performance, cost and other factors.

- How basic test and measurement equipment works, via hands-on experimentation leading to practical and usable tools at low cost.

- The basic design process, including math and algorithms, for the common, but not generally well-taught aspects of system-level mixed-signal design (e.g., how to deal with the fact that the real world seldom works like textbook examples nor problem sets).

In parallel, I had acquired the "VoidLoop" domains and my son Reid and his friend Andrew Chabot put together a very nice "placeholder" website. I really liked both the Arduino reference, but also the notion that there is a very productive positive feedback loop of sharing knowledge and learning in return… building something that grows and gets better over time.

Initially, what I put on the website are my Stanford course notes and my textbook on MEMS. We hope to supplement these with focused "design notes" on such topics as how to design manufacturable filters for antialiasing and signal reconstruction, practical level shifting techniques (often needed when using single-rail analog circuits), simple methods for generating negative supply rails, and so on. Of course, there is effectively an infinity of subject matter in electrical engineering, so the selection will be things that I feel are important to know, or potential pitfalls that are easily avoided.

Our work is aimed at students and hobbyists with moderate (not beginner) skill levels. We cannot offer basic tutorials on fundamental electronics, nor some kind of free consulting service. This is all about efficiently and broadly sharing what I think is interesting and useful information.

Philosophically, I'm focusing us on OS-free, powerful processors like the ARM M7 in the Teensy 4.1, where raw floating-point power is abundant, so even complex algorithms can be run, precisely and in real-time. Except for a downstream desktop application, code will be open-source (as-is, where-is, but thoughtfully designed). To keep the venture afloat, hardware will be sold on a semi-open basis (key schematic sections published, but not layouts and other details) at the lowest realistic cost. To enable that, I have been able to source bulk supplies of things like opamps, ADC's, and so on, as well as sometimes sourcing "recycled" chips (too expensive to purchase otherwise) carefully removed from circuit boards. With a limited, but well-chosen "menu" of mixed-signal chips, powerful processors and well-written code, many good things can be created.

Greg Kovacs

Palo Alto, California, September 2025